Introduction

The Southeast Asian maritime domain is vital to the region’s economic prosperity and security. It serves as a key conduit for trade and transportation and sustains the livelihoods of coastal communitiesamti.csis.org. Half of the world’s maritime trade traverses Indo-Pacific waters, underscoring the global importance of this regionmofa.go.kr. Beyond traditional security concerns like territorial disputes, ASEAN countries increasingly face non-traditional maritime security threats – issues that cross borders and fall outside the scope of conventional military challenges. These include transnational crimes, piracy, climate-related risks, and other challenges that no single nation can tackle aloneamti.csis.orgamti.csis.org. Recognizing this complex risk environment, ASEAN and its partners (including the Republic of Korea, ROK) have emphasized the need for enhanced cooperation to address non-traditional threats in the maritime realmasean.orgasean.org. The ASEAN-ROK Joint Statement on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership highlights a shared commitment to “tackling non-traditional and emerging security issues” and to “promoting cooperation on maritime safety and security” as part of a new era of deeper regional cooperationasean.orgasean.org. In this context, it is crucial to understand the key non-traditional maritime threats in Southeast Asia and to examine existing and potential avenues for cooperation between ASEAN countries and partners like South Korea.

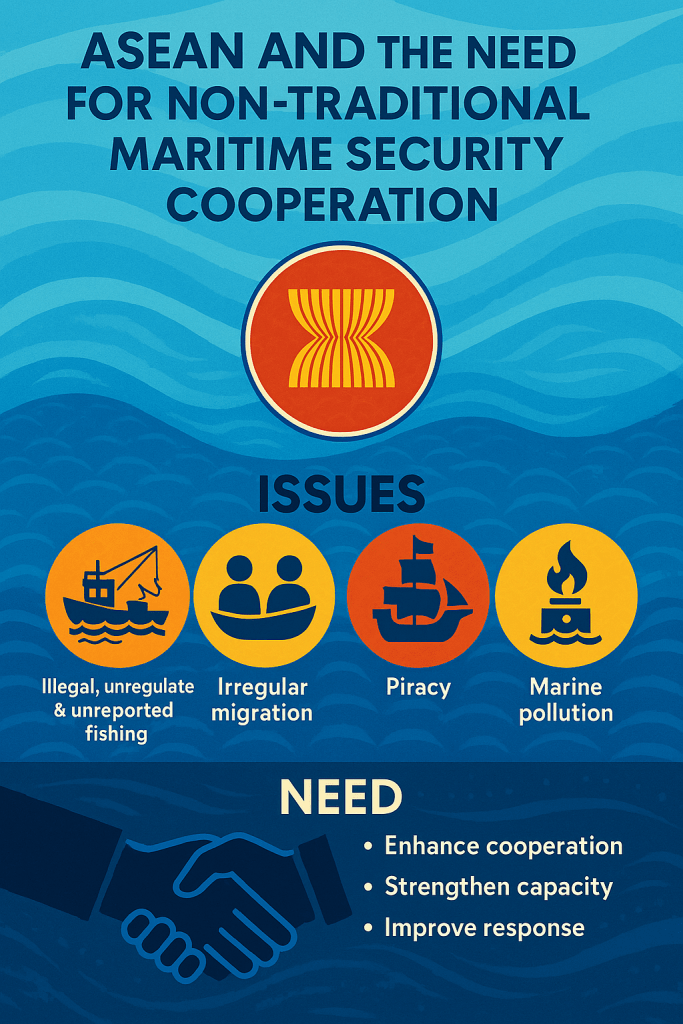

Key Non-Traditional Maritime Security Threats in Southeast Asia

ASEAN member states confront a range of non-traditional maritime security threats. These threats are transboundary in nature and often intertwined, requiring collaborative responses. Key challenges include:

- Piracy and Armed Sea Robbery: Southeast Asian waters have long been prone to piracy and hijackings. Incidents spiked in the 1990s and 2000s in hotspots such as the Malacca Straits and the Sulu-Sulawesi Seasamti.csis.orgamti.csis.org. A peak of 147 piracy and armed robbery cases was recorded in 2015 in Asian waterstransnav.eutransnav.eu, earning parts of the region the label of “the world’s most dangerous waters.” While regional efforts have since reduced such incidents, piracy remains a persistent concern that threatens shipping safety and regional commercetransnav.euipdefenseforum.com.

- Maritime Terrorism and Kidnapping: Terrorist groups have at times exploited maritime routes. For instance, the Abu Sayyaf Group’s kidnappings of sailors in the Sulu-Celebes Seas around 2016 alarmed the regionipdefenseforum.comipdefenseforum.com. High-profile attacks on vessels (e.g. SuperFerry 14 in 2004) demonstrated the potential for terrorism at seaamti.csis.org. These incidents underscore the risk posed by violent extremists to maritime security and the need for joint surveillance and response.

- Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing: IUU fishing depletes fish stocks, undermines food security, and erodes coastal economies. It is estimated that ASEAN countries lost over $6 billion in economic value to IUU fishing in 2019 aloneamti.csis.orgamti.csis.org. Indonesia – with one of the world’s largest EEZs – reportedly saw annual losses in the billions of dollars from illegal fishing, though aggressive crackdowns have reduced this in recent yearsamti.csis.org. IUU fishing is now recognized as a form of transnational organized crime, often linked to other offenses like human trafficking and forced labor on fishing vesselsamti.csis.orgamti.csis.org. The transboundary nature of fisheries and the mobility of illicit fishing fleets mean that no country can combat this threat in isolation.

- Marine Environmental Degradation and Climate Threats: Environmental issues are emerging as significant security concerns. Rising sea levels, coastal erosion, and extreme weather events threaten the safety of coastal communities and maritime infrastructureaseanindiacentre.org.inaseanindiacentre.org.in. The degradation of marine ecosystems – from coral reefs damaged by reclamation activities to pollution and plastic waste – has long-term security implications by endangering fisheries and livelihoodsaseanindiacentre.org.inaseanindiacentre.org.in. Southeast Asia’s vulnerability to climate change (e.g. stronger typhoons and flooding) means that maritime forces are increasingly called upon for humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) operations. Ensuring environmental security and disaster preparedness has thus become part of the non-traditional security agenda.

- Transnational Maritime Crime: The region’s vast maritime networks are exploited for smuggling of drugs, arms, and people. Traffickers use sea routes to move illicit goods across borders, as seen historically with narcotics trafficking from the Golden Triangle via maritime channelsamti.csis.orgamti.csis.org. Human smuggling and irregular migration by sea have also posed challenges for coastal states, requiring coordinated search-and-rescue and law enforcement. These crimes at sea not only threaten human security but also contribute to instability and violence in maritime areas.

Each of these non-traditional threats transcends national boundaries and overwhelms the capacity of any single ASEAN state. They also intersect with one another – for example, illegal fishing is linked with labor exploitation, and climate-related disasters can exacerbate conditions for piracy or trafficking. This interlinked nature reinforces the need for comprehensive and cooperative approaches. Indeed, ASEAN’s concept of security has evolved to acknowledge that protecting people, economies, and the marine environment is as important as defending territoryamti.csis.orgamti.csis.org. In the last decade, regional stakeholders have largely succeeded in suppressing traditional maritime threats like inter-state piracy and maritime terrorism, but new forms of insecurity have gained prominence, such as IUU fishing and climate changeamti.csis.org. Consequently, ASEAN countries increasingly view non-traditional maritime security cooperation as essential to regional stability and prosperity.

Existing Frameworks for Maritime Security Cooperation

ASEAN and its partners have established numerous frameworks and initiatives to address maritime security issues, many of which focus on non-traditional threats:

- ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting-Plus (ADMM-Plus): ASEAN’s multilateral security forums have incorporated maritime security cooperation into their agendas. The ARF, which includes 27 regional partners, adopted work plans and statements to encourage information-sharing, confidence-building, and capacity building in maritime security (e.g. the Hanoi Plan of Action in 2010)transnav.eu. Similarly, the ADMM-Plus (ASEAN plus eight dialogue partners, including ROK, the US, China, Japan, etc.) has an Experts’ Working Group on Maritime Security that convenes joint training and exercises. For example, multinational maritime security exercises and table-top discussions have been conducted under ADMM-Plus to practice piracy response, search-and-rescue, and HADR scenarios. South Korea has been an active participant in these efforts, attending ADMM-Plus maritime security meetings and drills alongside ASEAN members and other partnersworldjpn.net. These forums provide important platforms for dialogue, coordination, and capacity-building across the region.

- Regional Agreements and Centers: Southeast Asian states pioneered cooperative arrangements to combat maritime crime. A landmark initiative is the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP), the first government-to-government agreement in Asia to fight piracy. ReCAAP, which came into force in 2006, established an Information Sharing Centre (ISC) in Singapore to facilitate real-time sharing of piracy incident data and best practicess3-csis-web.s3.ap-southeast-1.amazonaws.com. Today, 21 countries (including several ASEAN members, ROK, Japan, India, and others) are contracting parties to ReCAAP, cooperating to reduce piracy across Asia. Singapore also hosts the Information Fusion Centre (IFC) – a regional maritime security center that has linked together 41 countries’ maritime agencies and stationed liaison officers from 25 countries, enabling collaborative monitoring of illicit activities at seas3-csis-web.s3.ap-southeast-1.amazonaws.coms3-csis-web.s3.ap-southeast-1.amazonaws.com. These hubs improve situational awareness and quick response to incidents such as piracy, smuggling, or maritime accidents.

- Bilateral and Trilateral Patrols: Sub-regional cooperative patrols have been effective in curbing specific threats. The Malacca Straits Patrols (involving Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and later Thailand) began in 2004 to jointly patrol one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, significantly reducing piracy in the Malacca Straitamti.csis.org. In the southern Philippines and Sulu-Sulawesi Sea, trilateral patrols known as INDOMALPHI (Indonesia-Malaysia-Philippines) were launched in 2017 in response to the spate of kidnappings by Abu Sayyaf. These coordinated air and sea patrols, along with intelligence sharing and Maritime Command Centers in each country, have been widely hailed as a success for sharply reducing piracy and kidnapping incidents in the Sulu Sea since their implementationipdefenseforum.comipdefenseforum.com. According to official Malaysian reports, the joint patrols led to a marked drop in kidnappings and armed robberies in the Sabah and Sulu waters after 2017ipdefenseforum.comipdefenseforum.com. Such patrol arrangements demonstrate the value of littoral states pooling resources to secure common waterways.

- Information Sharing and Training: Beyond patrols, ASEAN states cooperate through workshops, training exchanges, and information-sharing networks. Mechanisms like the ASEAN Maritime Forum and the Expanded ASEAN Maritime Forum (EAMF) bring together officials and experts to discuss maritime security cooperation, ranging from marine environmental protection to maritime law enforcement coordination. There are also initiatives focused on capacity building – for instance, joint training programs for coast guard and naval officers, and exchanges on legal frameworks to prosecute maritime crimes. These efforts, often supported by external partners (Japan, Australia, EU, ROK, etc.), help standardize practices and improve the interoperability of ASEAN countries’ maritime agencies.

Despite these numerous frameworks, one challenge has been overlap and fragmentation. Different agreements and forums sometimes tackle similar issues with limited coordination, straining the limited resources of ASEAN memberstransnav.eu. A 2022 study noted that the profusion of maritime security cooperative mechanisms – more than 30 in the South China Sea region alone – can lead to overlapping functions and reduced effectivenessglobal.chinadaily.com.cn. Nevertheless, the trend is clearly toward more cooperation rather than less. ASEAN has articulated a vision of “a peaceful, secure, and resilient regional maritime domain”, and its member states continue to seek the optimal structure to achieve that goal by possibly streamlining various effortstransnav.eutransnav.eu. In this regard, stronger partnerships with countries like South Korea, which is a dialogue partner and now a comprehensive strategic partner of ASEAN, are seen as a means to bolster regional initiatives.

Deepening ASEAN-ROK Maritime Security Cooperation

As a country with growing stakes in the Indo-Pacific, the Republic of Korea has been expanding security cooperation with ASEAN, especially in non-traditional security domains. Under its recent Indo-Pacific Strategy, Seoul explicitly pledged to “bolster comprehensive partnerships” with ASEAN across traditional and non-traditional security domainsmofa.go.kr. The elevation of ASEAN-ROK relations to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) in 2023 provides a diplomatic framework for more robust collaboration on maritime issuesasean.orgasean.org. Both sides have identified areas where Korean support and joint efforts can significantly enhance ASEAN’s maritime security capacity:

- Piracy and Maritime Law Enforcement: South Korea has been an active contributor to anti-piracy operations well beyond Northeast Asia. The ROK Navy has regularly deployed to the Gulf of Aden as part of the multinational Combined Task Force 151, even taking command of CTF-151 on multiple occasions alongside ASEAN partners like Singapores3-csis-web.s3.ap-southeast-1.amazonaws.com. This experience can be leveraged in Southeast Asian waters by sharing best practices in convoy escort, armed reconnaissance, and use of technology (e.g. surveillance drones) to combat piracy. Under the CSP, Korea and ASEAN have agreed to promote maritime safety and law enforcement cooperation, which could involve joint patrols or co-hosted exercises in piracy-prone areasasean.org. South Korea could also support the expansion of information-sharing networks by linking its naval/coast guard information systems with regional centers like the IFC and ReCAAP ISC.

- Combatting IUU Fishing and Enhancing Maritime Domain Awareness: Korea’s advanced coast guard and fisheries management experience position it to assist ASEAN states in tackling IUU fishing. Joint initiatives might include sharing satellite surveillance data and vessel tracking technology to monitor illicit fishing activities in real time. For example, Korea could contribute to the ASEAN Network for Combating IUU Fishing, which was established in 2020 to improve regional coordinationamti.csis.orgamti.csis.org. Capacity-building programs – such as training for fisheries enforcement officers or providing equipment (e.g. patrol vessels, radar systems) – would enhance the ability of ASEAN coastal states to detect and interdict illegal fishing vessels. Given that IUU fishing often involves vessels from outside Southeast Asia, Seoul’s diplomatic ties and its own crackdown on Korean distant-water fleets can complement ASEAN efforts through information exchange and coordination in fora like the Regional Plan of Action to Promote Responsible Fishing. By working together on sustainable fisheries and marine conservation, ASEAN and ROK can not only improve food security but also uphold international rules (like UNCLOS and the UN Fish Stocks Agreement) in regional waters.

- Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR): Natural disasters frequently strike ASEAN’s coastal communities – from typhoons and storm surges to tsunamis – requiring urgent maritime rescue and relief operations. South Korea, with its significant naval assets and disaster response expertise, can play a supportive role in regional HADR. Regular joint drills in disaster response (for example, under ADMM-Plus or EAS frameworks) and the pre-positioning of relief supplies and transport capabilities would improve collective readiness. The ROK Navy’s hospital ships or amphibious vessels could be integrated into multilateral exercises simulating maritime disaster scenarios. Furthermore, Korea can assist in strengthening early warning systems for maritime hazards (such as joint development of tsunami warning buoy networks or satellite weather monitoring) as part of a broader climate resilience partnership with ASEAN. Such cooperation aligns with the Indo-Pacific Strategy’s emphasis on contributing to regional public goods and addressing transnational challenges.

- Maritime Capacity Building and Training: A cornerstone of deeper cooperation is building up the human capital and institutional capacity of ASEAN states to manage maritime security. Korea and ASEAN have begun to organize joint workshops and training programs for maritime security personnelifans.go.kr. These cover skills like maritime law enforcement techniques, search-and-rescue coordination, port security, and cyber-security for port and vessel systems. Under the CSP, such programs could be expanded and institutionalized – for instance, establishing an ASEAN-ROK Maritime Security Training Center or annual ASEAN-ROK Maritime Security Dialogue. This would facilitate regular exchange of lessons learned and foster interoperability. Additionally, Korea’s defense and coast guard industries can contribute through technology transfers or co-development of surveillance and communications systems tailored for the complex geography of Southeast Asian archipelagos. Ensuring that all ASEAN members, regardless of size or capacity, can effectively police their waters and respond to incidents will increase overall regional security.

South Korea’s role as an ASEAN partner is viewed as relatively neutral and pragmatic, focused on mutual gains rather than geopolitical rivalrys3-csis-web.s3.ap-southeast-1.amazonaws.coms3-csis-web.s3.ap-southeast-1.amazonaws.com. This enables Seoul to act as a valuable “middle power” collaborator in ASEAN’s eyes – providing assistance without the baggage of great-power competition. Going forward, to maximize the impact of ASEAN-ROK maritime security cooperation, both sides should work towards coordinating their various initiatives under a cohesive agenda. This could mean aligning the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP)’s maritime cooperation priorities with specific projects in Korea’s Indo-Pacific Action Plan. For example, if the AOIP calls for protecting marine ecology and fisheries, an ASEAN-ROK project could focus on coral reef restoration or joint patrols in marine protected areas. Likewise, if combatting transnational crime is a priority, Korea could co-sponsor workshops on legal harmonization for prosecuting piracy and maritime crimes. Such alignment would ensure that cooperation is targeted at ASEAN’s most urgent needs and avoids duplication.

Conclusion

As ASEAN countries grapple with complex non-traditional maritime threats – from pirates and smugglers to climate-induced crises – cooperative security measures are no longer optional but imperative. Over the past decades, the region has built a tapestry of frameworks to address these challenges, laying the groundwork for trust and collective action. The partnership with the Republic of Korea adds an important dimension to this regional effort. By marrying ASEAN’s deep local knowledge with ROK’s resources and expertise, the two sides can develop innovative solutions for safer and more sustainable seas. The recent establishment of the ASEAN-ROK Comprehensive Strategic Partnership marks a “new era of deeper cooperation”, signaling high-level political will to elevate collaboration in maritime security and other fieldsasean.orgasean.org. To fulfill this promise, it will be essential to implement agreed plans of action, ensure all ASEAN members benefit equitably from cooperation initiatives, and maintain an inclusive, ASEAN-centric approach where external partners support (but do not overshadow) ASEAN’s role in regional security.

In sum, strengthening non-traditional maritime security cooperation with ASEAN countries serves the shared interests of both ASEAN and South Korea: it safeguards vital sea lanes and marine resources, enhances disaster resilience, counters illicit activities, and contributes to a stable, rules-based regional order. As challenges continue to evolve, so too must the cooperative mechanisms – emphasizing flexibility, information-sharing, and mutual capacity building. With robust commitment and coordinated action, ASEAN and its partners can ensure that Southeast Asia’s waters remain not only free and open, but also secure and thriving for the communities that depend on them.

References

[1] Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (CSIS) – “Southeast Asia’s Maritime Security Challenges: An Evolving Tapestry.” (2023). An analysis of the broad range of traditional and non-traditional threats in Southeast Asian waters and the region’s evolving responses. Accessed via AMTI (CSIS). Link

[2] Rosnani, D. Heryadi, Y.M. Yani & O. Sinaga – “Non-Traditional Maritime Security Threats: The Dynamic of ASEAN Cooperation.” TransNav, International Journal on Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation, Vol. 16, No. 3 (September 2022), pp. 419-426. This academic article examines ASEAN’s maritime security cooperation, noting overlapping efforts and the need for a more effective collective framework. Link

[3] Asmiati Malik – “IUU Fishing as an Evolving Threat to Southeast Asia’s Maritime Security.” (November 16, 2022). Part of the Evolving Threats to Southeast Asia’s Maritime Security series by AMTI/RSIS. Provides data on economic losses from illegal fishing and regional initiatives to combat IUU fishing. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (CSIS). Link

[4] Tom Abke – “Trilateral Air, Maritime Patrols Curtail Kidnappings.” Indo-Pacific Defense Forum, June 3, 2019. Describes the successful joint patrols by Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines (INDOMALPHI) in the Sulu-Celebes Seas that reduced incidents of piracy and kidnapping by extremist groups. Link

[5] Andrew W. Mantong & Waffa Kharisma (eds.) – “Navigating Uncharted Waters: Security Cooperation between ROK and ASEAN.” (November 2022, CSIS Indonesia). An edited volume exploring existing and potential security cooperation between South Korea and ASEAN. Contains a section on maritime security cooperation, including information on ROK and Singapore’s contributions to anti-piracy efforts (e.g. leadership in CTF-151) and regional centers like ReCAAP ISC and the IFC in Singapore. Full Text PDF

[6] ASEAN Secretariat – “Joint Statement on the Establishment of the ASEAN-Republic of Korea Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.” Adopted on 27 November 2023 (on the 35th Anniversary of ASEAN-ROK relations). This official document outlines the commitment of ASEAN and ROK to deepen cooperation, with specific references to enhancing dialogue through ASEAN-led mechanisms, tackling non-traditional security issues, and cooperating on maritime security and safety in accordance with international law (UNCLOS). Link (PDF)

[7] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Korea – “Introducing the Indo-Pacific Strategy.” (Seoul, 2022). The ROK’s Indo-Pacific Strategy framework, which emphasizes Korea’s commitment to a free, peaceful, and prosperous Indo-Pacific. Notably highlights Korea’s intent to “bolster comprehensive partnerships that encompass traditional and non-traditional security domains” with regional partners, including ASEAN. MOFA Official Website. Link

Leave a comment